Ozenfant in 1919 next to his self-portrait dating from 1918

Gaumont journal : « Purisme, a new School of Painting founded by Ozenfant and Jeanneret »

Digital copy of black and white silent film, 45 sec

©Courtesy Gaumont Pathé Archives

Amédée Ozenfant was born on April 15, 1886, in Saint-Quentin. He was the eldest son in a family of three. His father was a public works contractor, while his mother stayed home to raise her children. The family was well-off; his maternal grandmother also lived in the house, which was spacious and comfortable. His mother often traveled to Paris with her eldest son, attending exhibitions and museums.

Amédée was in fragile health; the northern climate did not suit him. Following pleurisy, he was sent to the warmer south, to a Dominican college in Arcachon, the Collège Saint-Elme. There, he produced his first drawings and watercolors. He enjoyed the visual arts, unlike classical studies, which he found boring and tedious. After completing his studies, he returned to Saint-Quentin after three years. In his hometown, he took private drawing lessons for a year from the director of the municipal school, Quentin Latour.

From the age of nineteen he often traveled in the afternoons through the surrounding countryside by bicycle with an easel on his back and began to produce some oils on the motif; in the morning he continued his training in drawing with several teachers. Sometimes he went back and forth to Paris and followed the decorative art courses of Maurice Verneuil and then Charles Cottet.

After a heated family discussion, he decided to move to Paris. His father agreed to finance his stay, on the condition that he take both painting and architecture classes in a studio, the Guichard et Lessage firm, on rue Saint-André des Arts in the Latin Quarter, not far from the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. This studio prepared him for entry into the Beaux-Arts. His father wanted him above all to become an architect to take over the family business he had created.

Very quickly, however, he abandoned architecture, to his father's despair. His mother supported him, influenced her husband, and his father finally agreed to continue to financially support his son, provided that his painting studies were followed seriously and assiduously.

Amédée Ozenfant then enrolled at the Académie de la Palette. Classes were taught by Dunoyer de Segonzac and Roger de la Fresnaye. At this time, Ozenfant read extensively, regularly attended concerts and the Opera, and frequented artistic circles, primarily the Symbolist ones. Unlike many other artists of the time, he led a comfortable life with no financial problems.

In 1908, he exhibited for the first time at the Salon of the National Society of Fine Arts.

He then met a young Russian artist, Zina de Klingber, at the Académie de La Palette.

Together they rent a studio in Montparnasse, on rue Campagne Première.

In 1910 he married Zina in St. Petersburg and from then on stayed with her several times in Russia, mainly in the small town of Perm.

The same year he exhibited at the Salon d’Automne under the name: Ozenfant de Klingberg.

His younger brother Jean, like him, was passionate about mechanics and they both decided to design and create a new body for a Hispano-Suiza, a luxury car of the time. This car was created and successfully presented at the Paris Motor Show in 1911.

1913. Ozenfant returns alone from his last trip to Russia. Zina stays with her family for several weeks before returning to the French capital.

1914. His brother Jean dies suddenly. Amédée leaves for the south of France, makes some graphite drawings that he will later consider to be works characteristic of the beginnings of purism; at the same time he meets the painter Paul Signac with whom he remains in contact. He is in Marseille when he learns of the outbreak of war and general mobilization. He is discharged for health reasons and leaves with his family for the southwest of France.

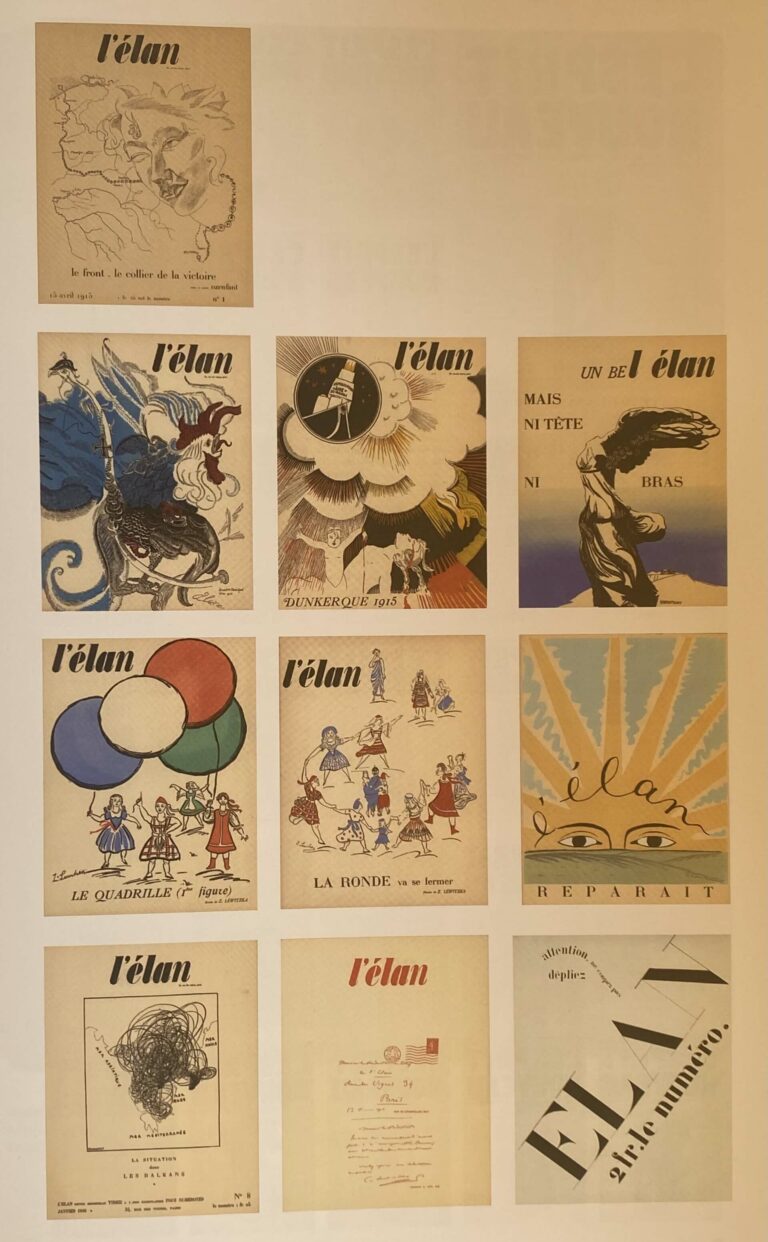

In 1915, Ozenfant, who was upset at having been discharged, wanted to contribute to the war effort in his own way. He then launched a magazine called L’Elan. This magazine was intended to be avant-garde and aimed at maintaining links with other artists of the time. He met Signac again, became acquainted with the Italian Gino Severini, and the Spaniard Juan Gris. Through contact with Severini, he successfully carried out typographic experiments. The poet Paul Fort contributed to the first issue, and the painters André Lhote, Metzinger, and Derain responded with illustrations and also with texts, such as those by Lhote, for example. Ozenfant published drawings with bold typographical creations. Guillaume Apollinaire also made extensive contributions. The magazine closed its doors the following year due to lack of financial resources, and in its last issue, Ozenfant put forward the term purism for the first time.

In 1917, his father Julien Ozenfant died, and the family public works company became a public limited company. The business then declined very quickly, as Amédée and his mother were unable to cope with the increasing difficulties. He met Germaine Bongard, sister of the couturier Paul Poiret. They had a fleeting relationship and lived together for a while.

Among the many intellectuals Amédée Ozenfant frequented, the architect Auguste Perret was very close to him. The latter offered to introduce him to one of his former draftsmen, a Swiss by origin: Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. A deep friendship bound the two men from the very beginning. Jeanneret, who had just left La Chaux-de-Fonds, unlike Ozenfant, had a somewhat narrow life. Born into a traditional Protestant family, he was under the thumb of a more than possessive mother. Jeanneret was shy, lived modestly, and had a mindset as narrow as his poorly cut suits.

On January 8, 1918, the two young men met for lunch and discussed painting. Ozenfant began to talk to him about his new ideas, about Cubism, which he did not view favorably, but especially about Purism and its new theories. Jeanneret had never painted in oils before. A few drawings, watercolors, but no real plastic technique. Cubism "made him laugh," it was very conventional, very classical in its tastes. His friend surprised him, challenged his choices, opened up unsuspected horizons in painting, he was seduced by this revolutionary discourse, which would later be called avant-garde. He was a young architect, Ozenfant suggested he become a painter!

Amédée Ozenfant says:

“In May 1917, I finally met Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. A new life was about to begin for him and for me. A sympathy, then a friendship developed: we both admired the masterpieces of modern industry, and Jeanneret had a sense of the very beautiful things of art, especially ancient ones, because he was still completely blind to Cubism, which made him shrug his shoulders; I introduced him to it and he soon changed his mind, I believe very sincerely. I received a long, moving letter from him, of which here are a few lines:

“…everything is in confusion within me since I started drawing again. Rushes of blood throw my fingers into arbitrariness, my mind no longer commands…I have discipline in my affairs, I have it neither in my heart nor in my ideas. I have let the habit of impulse live too much within me. In my dismay I evoke your calm, nervous, clear will. It seems to me that a gulf of age separates us. I feel myself on the threshold of study, you are at the stage of realizations. I see behind me the fluttering of thousands of intentions, of violent, successive sensations, and I always said to myself: one day I will build. When those days come I am a poor mason at the bottom of the excavation, without a plan!…You are…The one who seems to me to realize most clearly what is confusedly stirring within me…” (Paris, June 9, 1918).

From then on, the two friends spent long weekends in Andernos on the Arcachon Bay with other painter friends like André Lhote or writers and poets like Jean Cocteau. In March, Germaine Bongard set up a sewing workshop in Bordeaux, and Ozenfant alternated between Paris and Bordeaux. Ozenfant read Jeanneret his notes on purism and suggested that they sign their writings together and exhibit together. Jeanneret had never painted in oils; at that time, he had only produced a few gouaches. Ozenfant would teach him the techniques of oil painting. The two friends often met on Rue Gaudot de Mauroy in Paris in Ozenfant's studio, which he had taken over following his divorce from Zina Klingberg. It was in this studio that Jeanneret signed his first oil paintings.

Of course, Jeanneret immediately wrote to his mother in Switzerland to tell her about this meeting, this new friend, his emotions, his revelations, this new desire to paint. He explained to her how much Ozenfant was superior to him.

The relationship between Jeanneret and Ozenfant became close and quickly went beyond the simple stage of friendship.

After the armistice, the two friends agreed to produce a publication together, pompously titled Après le Cubisme. At the same time, they worked on a joint presentation to be held on Rue de Penthièvre in Paris at the premises of Germaine Bongard's fashion house. For this occasion, the premises were renamed Galerie Thomas.

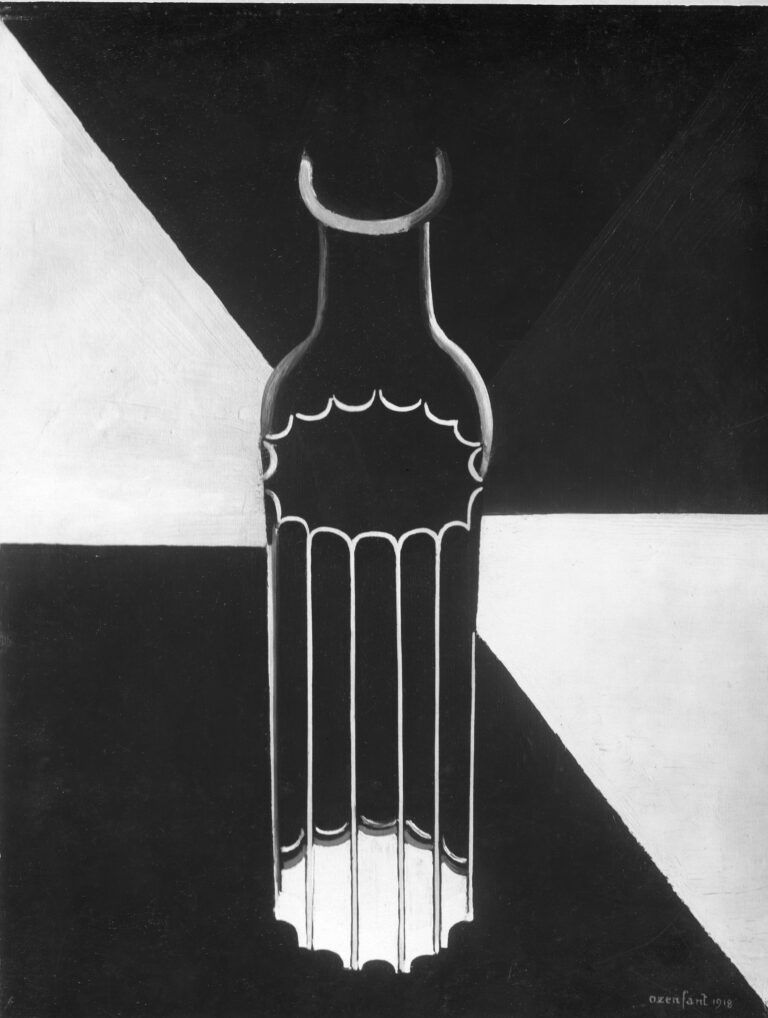

This exhibition can be considered as the antechamber of the purist movement; Ozenfant and Jeanneret used industrial objects from everyday life to create their still lifes: bottles, different glasses, vases, carafes. They only wanted to take from the objects their elementary quality in terms of their form and their colors, which Ozenfant defined some time later in the term invariant.

The exhibition catalogue is bound to the continuation of the small book Après le Cubisme and indicates that Ozenfant presents twenty works and Jeanneret ten. The preeminence of Ozenfant over Jeanneret is telling in this imbalance in the number of works between the two artists, but it is a preeminence consented to on the part of the young architect, his admiration for Ozenfant is such that it seems natural to him. Moreover, it was necessary to act quickly for this exhibition and Jeanneret does not yet have the necessary technical mastery.

As for the drawings exhibited at the Galerie Thomas, some of them are of great technical precision and reflect the purist message proposed by the two artists. For this, Ozenfant uses a new technique thanks essentially to a very fine lead, an excessively hard pencil called Koh-I-Noor 9H. The 1917 work Bottle, pipe and book also called Table, pipe, bottle, paper is a perfect example.

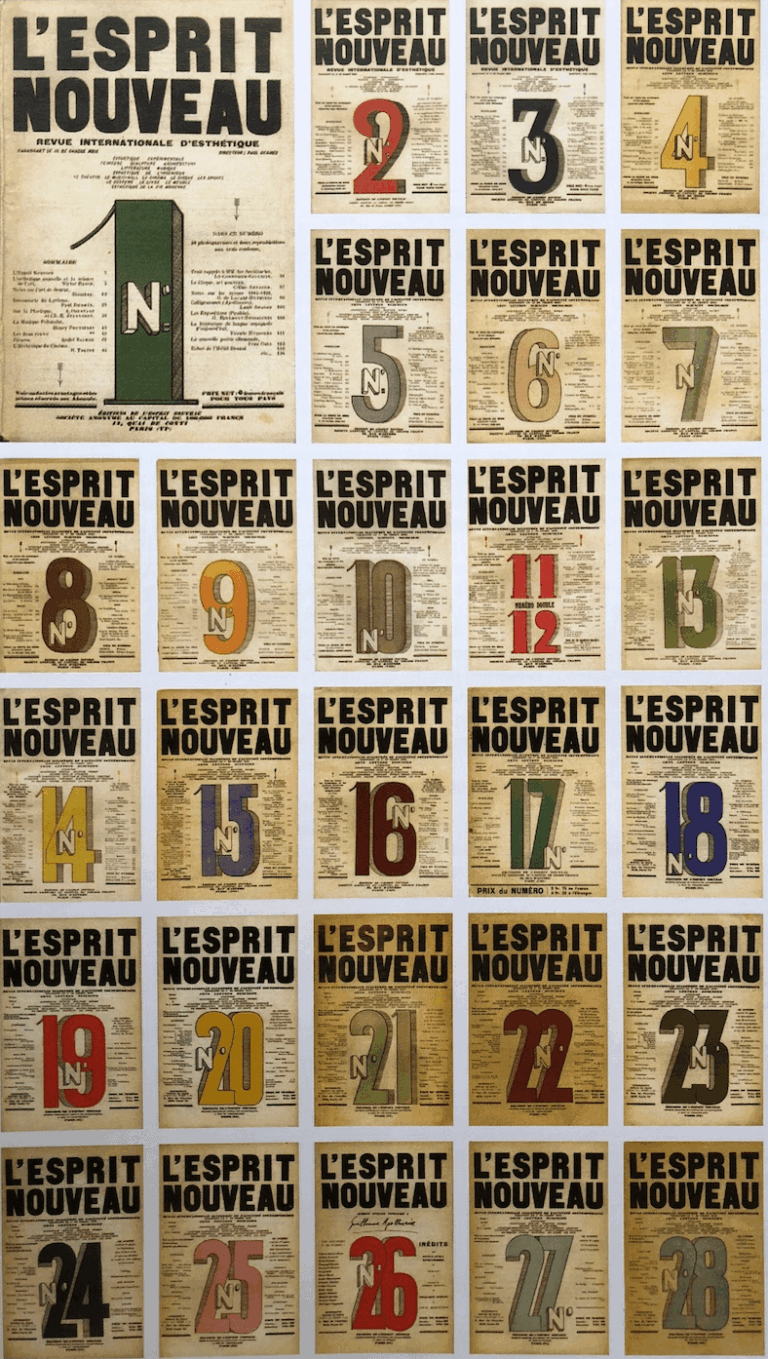

In 1919, Ozenfant met Paul Dermée, who had a project to create a magazine. Discussions took place between Dermée, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Ozenfant regarding the name of this magazine. The title L’Esprit Nouveau was chosen, probably at the initiative of the poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

Paul Dermée was the director of this new journal, Jeanneret took care of finances and Amédée Ozenfant became the artistic director with the choice of speakers, articles, illustrations, philosophical and aesthetic direction. The first issue was published on October 15, 1920. However, Jeanneret and Ozenfant decided to take over the co-direction of the journal and Dermée was dismissed from his position after only three issues.

To write in the Esprit Nouveau, Ozenfant often used pseudonyms at the beginning, such as Saugnier or Vaucrecy. It was at this time that he met Fernand Léger and a deep friendship was born. The two men had different personalities and did not come from the same social background, but the same vision of art and the same view of the emerging industrial society united them.

At the same time, other magazines and other artistic movements, such as Dada, appeared. Some artists adhered to purism while still being followers of Dada's ideas. While purism represented rigor at all levels, Dada used fantasy and provocation. While Jeanneret violently rejected Dada, Ozenfant remained more open and frequented certain circles, and above all, became friends with many artists such as Breton and the Russian painter Serge Charchoune, who was also very attracted to purism.

In 1921, the second Ozenfant and Jeanneret exhibition took place at the Druet gallery. In issue 4 of L’Esprit nouveau from January, we discover a landmark text on purism.

The principle of invariants is affirmed in this exhibition, the preparatory drawings allow us to understand Amédée Ozenfant's spirit of research. He uses an alphabet of forms that trigger constant sensations; triangles, circles, squares generate derivatives, thus creating a broader range but always having these invariants as a base. The colors are laid flat without any nuance. In this exhibition, the parity of the number of works is now respected; as many creations for Ozenfant as for Jeanneret. The creations resemble each other and it is often impossible to distinguish a work by Ozenfant or Jeanneret and vice versa.

Art critic Maurice Raynal seeks to establish differences between them; in Ozenfant, deduction and reflection appear to him to be more rational, whereas in Jeanneret, it seems more delicate and sensitive. Ozenfant plans and constructs his compositions logically, while Jeanneret develops them more instinctively. Each of their paintings is the subject of significant preparatory work, especially in Ozenfant's case. Numerous preparatory drawings or pastels precede the canvas for each work.

Ozenfant creates his drawings with very hard graphite, most of the time on laid paper or on paper that he makes himself.

Ozenfant was not only a genius theorist but he was also open to techniques often linked to the applied arts that developed during these years rich in creativity: photography, cinema, mechanics, radio and also the manufacture of different papers adapted either to the hard tip of the graphite lead, or to pastel or watercolor. The thicknesses of the papers are thus different depending on the media used; quite thick for watercolor, thinner for pastel or graphite lead.

Some time after the exhibition, Léonce Rosenberg contacted Ozenfant. He offered to exhibit some of his works in his gallery. Ozenfant signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg to be present at the next exhibition he was preparing every year in his gallery. This gallery was prestigious, renowned in the Parisian painting world. The exhibition took place from May 2 to 25, 1921. Ozenfant's paintings, like those of Jeanneret, were displayed alongside those of Picasso, Juan Gris, Mondrian, Braque, Herbin, and Gleizes.

That same year, Amédée Ozenfant met Raoul La Roche, a banker, Swiss citizen, with a substantial income and a great art lover. La Roche purchased several works from Ozenfant and also from Jeanneret.

Differences of opinion appeared more and more frequently within the management of L’Esprit Nouveau; Jeanneret and Ozenfant, each on their own, tried to put forward their point of view. They no longer agreed on how to run the magazine; increasingly vehement letters were sent from one side to the other. The climate deteriorated day by day and only worsened until Ozenfant resigned from his position as administrator of the magazine in 1925.

Despite the differences, a third and final joint exhibition took place from January to March 1923: Ozenfant and Jeanneret at Léonce Rosenberg's L’Effort Moderne gallery, rue de Baume in Paris.

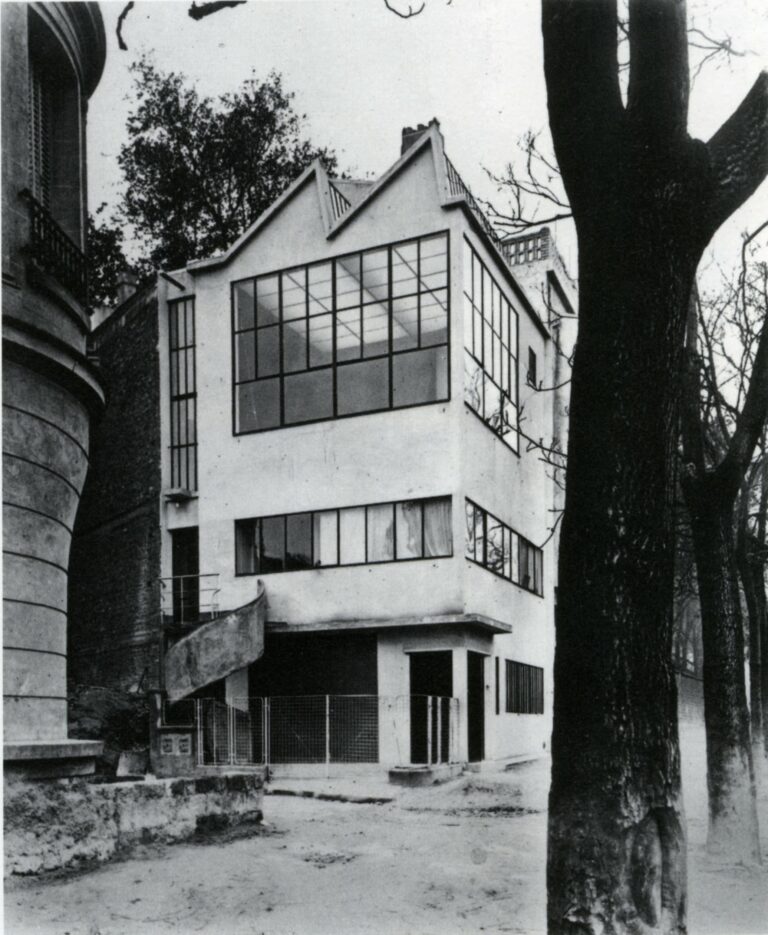

Despite these disagreements, Ozenfant asked his friend to build him a house-studio according to his own sketches, with very precise specifications. The man who now adopted the name Le Corbusier accepted the commission and, with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, began the construction of the building on Avenue Reille in Paris. In 1924, after two years of work, the house-studio was practically finished.

Despite their differences of opinion and his departure from the Esprit Nouveau, Ozenfant published another major work with Le Corbusier in the summer of 1925, La Peinture Moderne. This work constituted the final intellectual collaboration between the two purist brothers. He exhibited his work in the Pavillon de l'Esprit Nouveau, built by Le Corbusier as part of the Salon International des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Also featured at this exhibition were Mondrian, Gris, Lipchitz, Braque, and many other artists faithful to the purism and fundamental principles of this Esprit Nouveau.

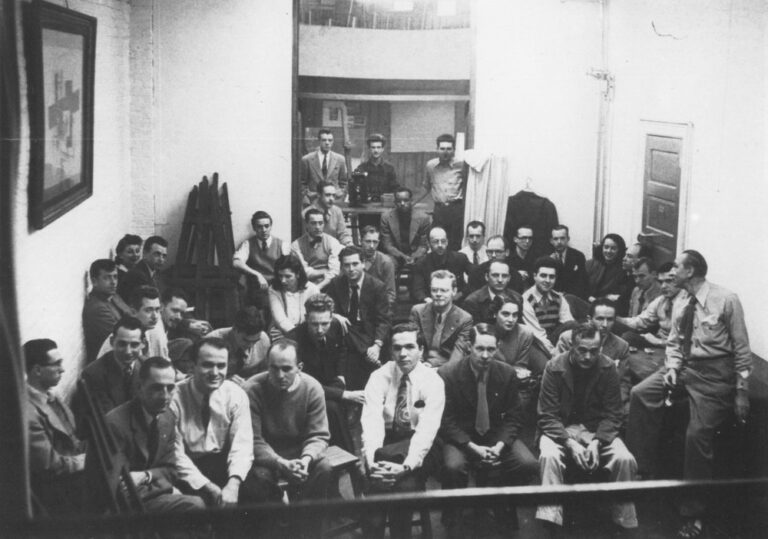

Between 1926 and 1930, Ozenfant gave his painted compositions a more significant, monumental dimension. He used forms with architectural evocations. During this pivotal period of production, Ozenfant worked with Léger and taught at the Académie Moderne, which they had created; he often replaced Fernand Léger in his teaching or worked alternately with him, until the beginning of 1929. The Académie Moderne was attended at this time by Clausen, Marcelle Cahn and by the woman who would become Madame Fernand Léger. Many other well-known artists today followed the teachings of the Académie Moderne.

The year 1926 would see the confirmation of Le Corbusier's talent as an architect at the international level. The difficulties of the Esprit Nouveau, this ascendant success of Le Corbusier would increase the dissensions between Ozenfant and his architect friend; the two brothers, the two inseparable ones, would definitively take opposite paths. The letters exchanged became increasingly violent and engendered contempt, a mutual hatred. The brothers, enemies of purism, would not see each other again for many years. Their respective excessive egos would certainly prevent them from taking "a first remedial step" and forgetting previous disagreements. Le Corbusier, in fact, no longer accepted being under the thumb of the one who had taught him everything; not only painting but also a certain way of being in a refined intellectual environment that was not his to begin with. He wanted to forget, to ignore the one who was his master and to pass definitively from the shadows into the sun. Ozenfant is aware of Jeanneret's weaknesses and the latter can no longer stand him; he is now Le Corbusier, thirsty for artistic and social recognition.

During this same year, Amédée Ozenfant met a young woman, Marthe-Thérèse Marteau. The latter worked as a milliner for the great couturier Jean Patou. They married and jointly opened their own fashion house, Place de la Trinité in Paris. The fashion house took the name: Amédée. This fashion house allowed the young couple to breathe a little financially; commissions for paintings were rare and times were becoming difficult for artistic creation and the art market. Of course, Le Corbusier denigrated this initiative and did not miss an opportunity to publicly and openly mock his friend Ozenfant by stating that couture was not worthy of an artist, a creator, a painter.

The year 1926 was also the year when Ozenfant began large mural compositions, just like his friend Fernand Léger.

In 1927, Ozenfant broke with the iconography and formal principles of purism. He reintroduced the human figure into his paintings, for example with a bold and remarkable oil on canvas: Woman and Child

The following year, Ozenfant published Art. The book presents itself as a review of modern art while presenting a new spirit, a new aesthetic. The Hodebert-Barbazanges gallery organized its first solo exhibition in Paris.

In 1930 Amédée Ozenfant participated in several exhibitions of the post-cubist movement Cercle et Carré, exhibitions in which he met painter friends who were already present in his magazine L’Esprit Nouveau.

He traveled extensively, mainly in Germany, and successfully gave lectures in various cities: Berlin, Dessau, Hanover, and Hamburg. He met the architect Eric Mendelsohn, who admired his paintings. Mendelshon commissioned several decorative ensembles, frescoes, and wall panels for his villa in Berlin.

During this German trip he took the opportunity to visit the Bauhaus in Dessau.

Back in Paris in 1932, he opened the Ozenfant Academy in his studio on Avenue Reille, where he trained many students, including Henri Goetz.

After several trips to Greece and Turkey, he returned to England, where he met other artists. He enjoyed life in London. Social events in France were increasing, life was becoming difficult, and after several trips back and forth, he considered transferring his painting academy to England.

In 1936, he moved to London with his wife Marthe and opened the Ozenfant Academy shortly after, in May. He took the opportunity to perfect his English, a language he particularly loved. He continued to travel between Paris and London, giving classes at the Lycée Français in London and the Institut Français. In 1938, he published a book, Tour de Grèce.

During the summer of 1938, he left for the United States at the invitation of the painter Jean Lurçat, where he gave a few lectures at the University of Seattle. He traveled part of the United States by bus with his wife and they liked the country. In Europe, worrying events had been occurring for some time; Ozenfant was worried; he returned to London and moved to New York in February 1939.

In his memoirs, Ozenfant describes this arrival by boat in New York with enthusiasm. He is happy to discover the new world, walks the streets of New York with Marthe: clearly a new life is opening up to him, he is simply happy, full of projects.

He opened a painting academy again at the end of July: the Ozenfant School of Fine Arts. He published Journey through Life in English the same year. New York awaited him and opened up to him with encounters, new experiences, exhibitions, and official commissions.

In 1940, the Art Club of Chicago organized a solo exhibition for him; this exhibition traveled to the state of Minnesota in Saint Paul as part of the Gallery and School of Art, as well as to Michigan: Ann Arbor University. The American public discovered him and he sold several works.

The Bignou Gallery in New York exhibited his work in 1941, as did the Passedoit Gallery in New York and then the Nierendorf Gallery in Berlin. Ozenfant participated very early on and for many years in La Voix de l'Amérique, a radio program created by journalist Pierre Lazareff and Lewis Galantière; many refugees would lend their voices to this resistance radio station. In France, it represented intellectual resistance through renowned artists who had left Europe.

In 1944 Ozenfant became a naturalized American citizen. His painting was appreciated in the United States of America, he felt at home there and his school was now enjoying real success in New York.

In 1949 he received the Legion of Honor from the French State.

He created a series of paintings of America, its skyscrapers, its buildings illuminated at night, its bridges. He also fulfilled commissions from several states for public buildings.

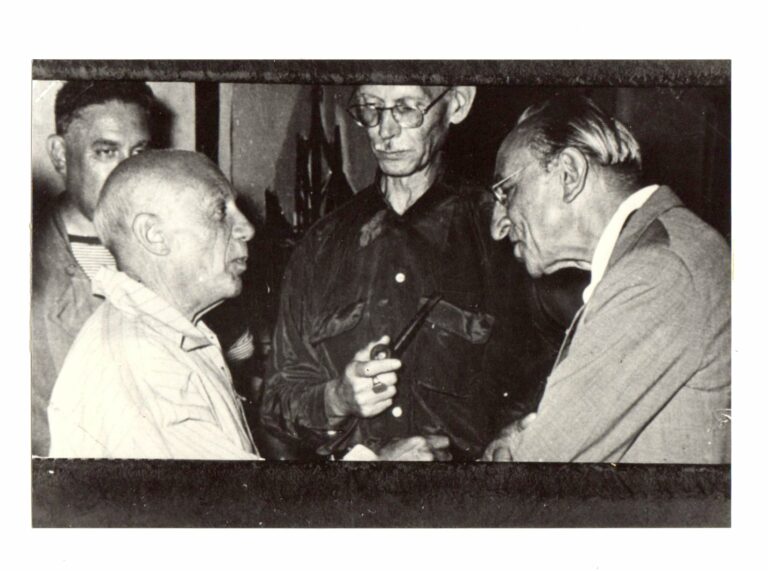

From 1952 onwards, he returned to France several times to spend the summer, visiting his friend Picasso in the south, in Vallauris or Cannes. He participated in the Sao Paulo Biennale. He missed France, but he was now better known in the United States than in France, and the decision to return was difficult. No one expected him in France any more, and official art circles were turning their backs on him somewhat.

It was an American who organized a special exhibition for him in Paris in his gallery: Edwin Livengood, who had lived in the capital for many years and who had obviously heard of Amédée Ozenfant: an exhibition therefore at the Berrien gallery in 1954, then at the Berri-Lardy gallery this time in 1956.

Ozenfant returns to France with his wife Marthe. The return is less glorious; he has very little money left, and the problems begin as soon as the crates containing not only his personal belongings but also hundreds of works on paper and canvases are unloaded. Following a misstep by dockers, a container falls into the port of Marseille with all of his creations. Recovering the contents takes several hours, and all the works on paper are permanently lost, as are his personal archives and books. Amédée Ozenfant is desperate and devastated. He settles permanently on the French Riviera, in Cannes.

Ozenfant regained French nationality and renounced his American passport; after several failed attempts at solo exhibitions, he had a decisive encounter. A friend introduced him to Katia Granoff, who had a major gallery in Paris. Katia was captivated by the man and the artist; she organized his first solo exhibition. The exhibition was a success, the first sales came in, and collectors gradually opened their doors. Amédée, however, continued to give lessons at his home to a few students, because teaching and passing on knowledge were important to him.

In 1962 he signed a contract with Katia Granoff. Life became more serene; there were no more money worries. Katia bought everything he produced and he could now paint in peace, without fear of tomorrow. That same year he was named an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters.

Katia Granoff's exhibitions followed one another in Paris and Cannes. In 1964, the Château Musée de Cagnes-sur-Mer also dedicated an exhibition to her.

In 1966, he died in his adopted city following an operation, and two years later, Katia Granoff published the Memoirs of her friend Ozenfant. These memoirs are rich in anecdotes and provide an intimate insight into the art world over several decades, both in France and the United States. His wife died a few years later. The Ozenfant family had no children and no heirs. Marthe left their Cannes apartment, along with everything it contained, to the caretaker couple of their building. They had devotedly cared for them in the last years of their lives, and it was only natural for Marthe to designate them as her heirs.

While a significant portion of the paintings returned to Katia Granoff according to Amédée Ozenfant's wishes, an equally significant portion that remained in the apartment after Marthe's death returned to their faithful guardians. Many works on paper: pastels, watercolors, and gouaches thus disappeared from the art market, as did many personal archives: correspondence, personal writings, etc.

Ozenfant left his mark on the first half of the twentieth century. The purist movement, of which he was the true initiator and theoretician, would influence artists from all over the world, and it can be said that this aesthetic movement would retain for years to come a freshness and authenticity worthy of the crystal sought by its creator.