Séraphine Louis was born on September 3, 1864, in a small village in the Oise department called Arsy, not far from Compiègne. Her father, Antoine Louis, was a “laborer,” usually hired by the day, and an occasional clockmaker. Her mother, Victorine Adeline Maillard, who was born on December 18, 1827, cleaned houses. Antoine and Victorine were married on December 30, 1847. Seraphine is an orphan very young. dans un petit village de l’Oise qui se situe non loin de Compiègne, le village d’Arsy Le père de Séraphine, Antoine LOUIS est « manouvrier », journalier la plupart du temps et horloger à l’occasion. La mère, Victorine Adeline Maillard née le 18 décembre 1827, femme de journées, fait des ménages. Antoine et Victorine se marient le 30 décembre 1847. Séraphine est orpheline très jeune.

We know little about Séraphine’s childhood. Séraphine took care of the farm animals and helped with field work. She lived in great poverty. Her daily life was hard and the little girl didn’t always have enough to eat.

At age eighteen, she went to work as domestic help for the nuns in Clermont at the Convent of the Charity of Providence. She would stay there for twenty years, but did not become a nun.

Séraphine was recommended for a job in the home of a lawyer named Chambard in 1905. She stayed there for several months and then worked for various middle-class families in Senlis. Each time she lived with the families, and she did not like this. She felt hemmed in at other people's homes, with no privacy.

In 1906, she finally rented her first apartment on Rue du Puits-Tiphaine in Senlis. The place was modest and not very large. It had ceilings that were over thirteen feet high. She finally had a home of her own. She was forty-two years old, and it is surely on Rue du Puits-Tiphaine that she painted her first works.

On Rue du Puits-Tiphaine, Séraphine lived not far from the cathedral. She went there every day to pray, especially to pray to Mary. What was the source of this transformation, which took place gradually but inexorably in the deepest reaches of herself? Séraphine drew closer to Mary through prayer but another phenomenon that was strange and mysterious appeared: a slow, inevitable transformation of her entire being, independent of her own consciousness, that pushed her to draw, to paint, to create. At this time, Séraphine worked for the Duflos family. The mother, Irma Duflos, had a milliner’s studio. One of the children, Pierre, had a little watercolor set, and after a few tries in pencil, Séraphine made a modest watercolor for the first time on plain paper.

Of course, Séraphine had no technical knowledge and no one at her side to give her advice or directions. She painted alone, with no help. She then had the idea of buying a jar of Ripolin that she discovered in a hardware store in Senlis. Séraphine made her first attempts on cardboard, which she covered entirely with paint to make a background for her first paintings. sur lequel elle réalise ses premières peintures.

When Séraphine had a few hours of freedom, on Sunday, she roamed the countryside, gathering flowers, branches, lichen, earth, and feathers. Back in her apartment, she would grind these ingredients carefully in pots, reducing them to powder or paste that she then mixed with white Ripolin. Somewhat later, she even used blood that she collected when a chicken was killed for Sunday dinner, or when a pig was bled at a neighboring farm.

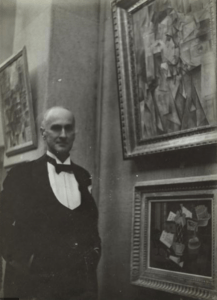

Around 1912 or 1913, Séraphine’s routine was transformed by the arrival of a strange figure: Wilhelm Uhde, a German collector, writer, critic, and art dealer. He bought by chance a small work of Séraphine: la nature morte aux pommes.

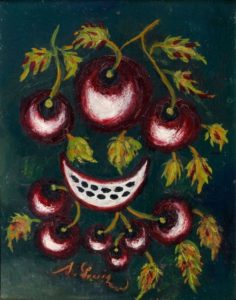

He meets Séraphine and he bought four or five other paintings that were similar to Nature Morte aux Pommes. The subjects were also fruits an orange, a bunch of grapes and the works were also small, painted on cardboard or small wood panels that Séraphine found here and there. We do not know how many paintings Wilhelm Uhde really bought from Séraphine at this time. It is also difficult to understand how Séraphine’s work developed after this first meeting with Uhde her artistic technique, and her choice of subjects from 1912 to 1920.

It is difficult, even impossible, to reconstruct exactly Séraphine’s artistic development before 1920, and it is also very difficult to establish a true chronology before 1927.

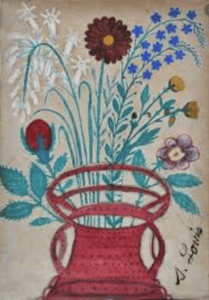

Flowers gradually appeared, as in a composition from 1920 Fleurs au Fond Bleu This was probably the first artwork with flowers, simple ones in the foreground on a blue background. The depiction of the flowers is still basic, with a childish or even awkward design, with green leaves arranged around them as decoration.

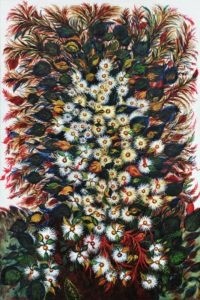

Right afterwards, Séraphine took on a larger format, 81 X 60 cm, with another bouquet, Marguerites, with a noticeably more structured composition. The transition between these two paintings was important and announced a real technical development and a new phase that Séraphine had entered, even if the composition of the white daisies that were still floating nevertheless had a certain awkwardness that would gradually disappear over the following years.

But what happened to Uhde with the start of World War I? He had to leave France and return to Germany. Senlis was occupied by foreign troops. The city burned in the invasion, and many buildings were destroyed.

How could she not have been troubled and disturbed during a time of war with this double life of servant and painter?

In 1927, the organization The Art’s Friends Society from Senlislaunched the idea of an art exhibition in Senlis. It was intended to illustrate all aspects of artistic creativity in the town. It was open to both professionals and amateurs. Séraphine will exhibit six paintings.

The Paris press wrote a glowing tribute to Séraphine and considered her the true revelation of the exhibition. Having returned to Paris after the end of the war, Wilhelm Uhde heard about this exhibition. He seemed then to remember his former maid, and decided to go to Senlis immediately.

After Uhde's return in 1927, it seems clear that an artistic change occurred once again in Séraphine Louis’s aesthetic development and in her choice of themes. The dealer’s influence was fundamental to her art and therefore to the career that was henceforth beginning for her. There was a sort of reciprocal trust between Séraphine and Uhde.

The 1927 exhibition in Senlis revealed Séraphine's work to the public in Paris, to Parisian collectors, and to reviewers in the press. After this date, Séraphine regularly sold her artwork and could stop working for other people and devote herself to her art. However, by this time Séraphine was already an old woman, worn out by a life of labor, bullying, and lack of respect. She was sixty-three years old. She was tired, and unfortunately she lost a little more of her mental faculties every day. She engaged in strange behavior that confused those around her and encouraged gossip. There was much talk of her in town, and many Senlisiens, through jealousy and baseless cruelty, spoke negatively about her on a regular basis.

Thanks to Wilhelm Uhde, Séraphine's art was now appreciated internationally, in Germany, naturally, but also very soon in Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the U.S. Séraphine was more sure of her art. She now held her head up, as in one of the few photos of her, taken by Anne-Marie Uhde, where she poses in front of her easel with a palette in her hand — a thin, shriveled little country woman, but proud of her painting having finally been recognized.

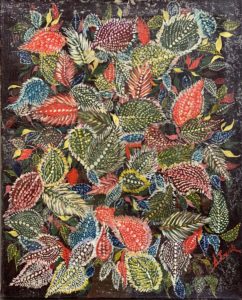

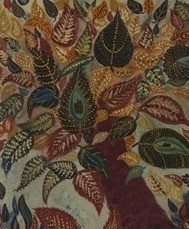

From 1928 to 1930, she created her finest paintings, which were the most accomplished and also the most symbolic: Les Grandes feuilles, L’Arbre Rouge in 1928 as well as Grappes de Raisins and L’Arbre de Vie; in 1929, Arbre et Feuilles d’Automne, Les Fruits, and Marguerites, Feuilles. Marguerites, Feuilles Her compositions primarily depicted flowers, leaves, and fruits, and she combined real and fantastic elements. What species are these flowers that look at you, flowers surrounded by fur? With Arbre du Paradis in 1929, the eye in the center of the painting has a haunting presence. It chills the viewer, creating anxiety with this sort of pointed beak that is ready to jab and bite. The trunk of the tree, with its very unusual artistic depiction, seems to be burning, almost untouchable. This may be the painting in which Séraphine expresses herself the most and in which, at the same time, she protects herself from others.

During this period of success, Séraphine experienced comfort and peace. She was more sure of herself and did not doubt the quality of her work.

Wilhelm Uhde bought everything the artist painted. His sister, Anne-Marie Uhde, who came to Chantilly in 1927, visited Séraphine for the first time that same year, according to her own account. ; the two women got along well and appreciated each other, and Séraphine often agreed to receive Anne-Marie in her small apartment where they would talk together.

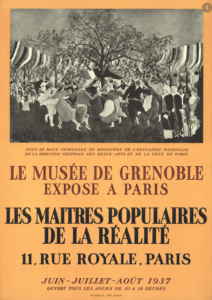

It was thus a prosperous and glorious time for Séraphine Louis. Everything was going her way, and it went to her head. She was regularly informed of newspaper articles discussing her in Paris, Germany, and even America. Uhde wrote to her that her paintings were now found in renowned collections all over the world. In 1928, he arranged for her first participation in an exhibition in Paris, bringing together The Painters of the Sacred Heart at the Galerie des Quatre Chemins, and it was very successful. Increasing numbers of important collectors discovered her art and bought her paintings. Les Peintres du Cœur Sacré àla Galerie des Quatre Chemins. Des collectionneurs importants toujours plus nombreux, découvrent sa peinture et achètent alors ses œuvres.

However, in 1929, the financial crisis approached, and business became difficult for Wilhelm Uhde. The art market was affected like all other sectors of the economy, and buyers became scarce.

Uhde urgently asked Séraphine to reduce her expenses, but, as discussed above, she lived in her own world, and she did not understand the concerns of her dealer friend.

In late 1930, Uhde stopped supporting Séraphine, citing his financial difficulties due to the economic crisis. But Séraphine could not understand why Uhde was worried. She was devastated and thought that her dealer no longer did a good job representing her work, that he was no longer able to sell. She withdrew further into herself, stopped eating and sleeping, and very soon stopped painting. She collapsed physically and psychologically.

For Séraphine, Uhde was abandoning her once again. Everything collapsed once more around her, as it did during the war years of 1914 to 1918, following his first departure. That earlier departure could be explained by the war, but now there was no justification — on the contrary, she felt that it was a betrayal. She could not understand!

This was the beginning of madness that would not end. Séraphine went door to door announcing the end of the world. She stated that evil people would be punished, that the world would collapse. She felt persecuted and thought that people would rob her or, even worse, rape her in her sleep.

Very soon, the police were informed and realized where all these items came from. They informed the police commissioner, Mr. Rasmer, who, after a brief investigation, decided to have Séraphine immediately admitted to the Senlis hospital, declaring that Séraphine Louis had lost all reason, represented a danger to herself, and was unable to feed herself or to provide for her own needs. Dr. Bellot, a medical examiner, examined her and wrote up a report stating that she was affected with a mental handicap and that her condition required her to be cared for in a home for the elderly. décide de faire admettre Séraphine d’urgence à l’Hôpital de Senlis, jugeant que la dénommée Séraphine Louis, privée de tout jugement, représente un danger pour sa propre personne, qu’elle est incapable de se nourrir et de subvenir seule à ses besoins. Un médecin légiste, le docteur Bellot l’examine et établit un rapport soulignant à son tour que la malade est atteinte de débilité mentale et que son état nécessite qu’elle soit dirigée vers un asile de vieillards afin de pourvoir à ses besoins vitaux.

Séraphine stayed in the Senlis hospital for a while. The doctors tried to reassure and calm her, and gave her medication to reduce her anxiety, but in vain. On February 25, 1932, she definitively left Senlis and was admitted into the home in Clermont sur Oise.

Séraphine stayed in this hospital for ten years and stopped painting. She asked for writing materials, but never for painting materials.

This is not a place for working on arts (sic) and I don’t have anything I need to work here… as far as food I am constantly a victim, I have no comfort (sic)

Writing gradually became a vital necessity for Séraphine Louis. She survived partly due to her writing. With her own words, she remembered her past and also developed her obsessions, accusing those who wished her harm. She constantly complained of hunger. pour Séraphine Louis, elle survit grâce en partie à l’écriture. Avec ses mots à elle, elle se souvient de son passé, développe également ses obsessions, accuse ceux qui lui veulent du mal, se plaint de la faim constamment.

Meanwhile, for Séraphine Louis-Maillard, the years passed slowly, very slowly, and no one thought about her, not even Monsieur. Clearly, he had forgotten her once again. monsieur, il l’a visiblement oubliée, une fois de plus.

The war had been raging for over two years, and would only further degrade the conditions at the Clermont hospital.

Séraphine Louis slowly perished, gaunt, worn-out, and suffering from breast cancer, on December 11, 1942. She would never again see Senlis, her cathedral, Rue du Puits-Tiphaine, or Monsieur. monsieur…

At the end of his book Cinq Maîtres Primitifs, in the part on Séraphine, Wilhelm Uhde writes:

The art I am discussing is one-of-a-kind. Its creation is uncontrollable. It escapes the laws that usually regulate painting, although it satisfies its most intimate requirements. Although this oeuvre is made up of paintings that, as such, are of great quality, it is more than the sum of good paintings. The rules of artistic creation, the Western style, the personal or feminine element seem to have nothing to do with it. One must be in some kind of state of grace first to understand this art, and then to respect and accept it.

If one wants to find the origins of this phenomenon that can be considered unique in the history of painting, it must be stated first of all that Séraphine’s painting is connected to no movement, imitation, school, or influence of any kind.

Although her oeuvre contains only very few paintings today, it remains very present across time and remains unique in the history of painting.